Mewing Before & After: Jawline Transformation Photos!

Can a simple technique reshape your face and jawline? The practice of "mewing," a self-described facial posture exercise, promises dramatic transformations, with enthusiasts claiming visible changes in facial structure over time. The allure of non-invasive aesthetics, achievable through consistent effort, has captivated a global audience, but the scientific rigor behind these claims warrants a closer examination.

The core principle of mewing involves the conscious positioning of the tongue against the roof of the mouth. The proponents suggest that maintaining this posture throughout the day with the entire tongue, including the back third, pressed against the palate can influence facial development and reshape the jawline. They posit that this consistent pressure encourages the upper and lower jaws to expand, leading to a more defined bone structure, a straighter profile, and enhanced facial symmetry. The practice, named after Dr. Mike Mew, a British orthodontist, and his son, Dr. John Mew, has garnered both fervent supporters and skeptical critics. Before-and-after photographs and anecdotal accounts abound online, fueling the debate surrounding the efficacy and validity of mewing.

Before delving further into the scientific basis and practical application of mewing, its crucial to address the fundamental questions that arise when considering any aesthetic intervention. Does it work? Is it safe? What are the realistic expectations? The answers, as with many things in the realm of human biology, are complex and nuanced. The observed results, both in terms of before-and-after appearances and in the medical literature, are inconsistent. While the concept is relatively new to the mainstream, its origins are embedded in the field of orthodontics. Historically, there has been emphasis on the impact of tongue posture on the development of dental and facial structures. This concept is linked to understanding the impact of mouth breathing habits, as they affect bone growth. The underlying principles hinge on the malleability of bone and soft tissue, particularly during the formative years of development. However, mewing, as a standalone technique, operates outside of established orthodontic practices, presenting a different set of challenges in terms of validation.

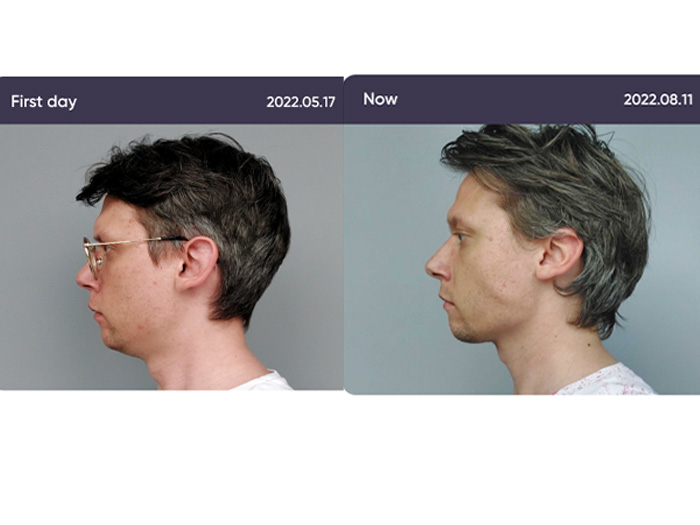

The most compelling argument for mewing is often presented through visual evidence. Countless images and videos circulate online, depicting individuals claiming to have achieved significant changes in their facial features through the practice. These "before-and-after" comparisons frequently showcase alterations in jawline definition, cheekbone prominence, and overall facial symmetry. Some proponents point to the potential for improved nasal breathing, a reduction in double chins, and a subtle upward shift in the facial profile. However, assessing the validity of such visual evidence can be problematic. Factors such as lighting, angles, photo editing, weight fluctuations, and natural aging can all influence the perceived changes in appearance. Without rigorous scientific controls and objective measurements, its difficult to determine the extent to which mewing is responsible for the observed transformations. The subjective nature of these comparisons underscores the need for a more critical approach.

The scientific foundation of mewing, or the lack thereof, is a point of contention. While the concept of tongue posture influencing facial development has a basis in orthodontic principles, the specific claims made by mewing advocates are largely unsupported by robust, peer-reviewed research. The primary mechanism of action, as proposed by mewing, involves applying pressure from the tongue to the palate. This is believed to stimulate bone remodeling and encourage forward growth of the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw). However, the scientific literature on the subject is limited. While some studies have explored the impact of tongue posture on dental alignment and craniofacial growth in children, the evidence supporting the efficacy of mewing in adults is scarce. The existing research primarily focuses on established orthodontic treatments and interventions, rather than self-directed techniques. The difficulty of conducting controlled studies on mewing, coupled with the challenges in isolating its effects from other variables, further complicates the situation.

The biological principles governing facial growth and development are complex. During childhood and adolescence, the bones and soft tissues of the face are relatively pliable, making them more susceptible to external influences. The practice of tongue posture could, in theory, play a role in shaping the developing facial structure. However, as an individual ages, the bones of the face become less malleable. In adulthood, significant changes in facial structure are more challenging to achieve without surgical intervention or orthodontic treatment. The proponents of mewing assert that even in adulthood, consistent tongue pressure can stimulate bone remodeling. It's a phenomenon, to some extent, but this claim, lacks sufficient scientific support. The body's natural processes of aging and the effects of genetics also play a significant role in the appearance of the face, making it challenging to isolate the effects of any single technique.

One of the key concerns surrounding mewing is the potential for negative side effects. While the practice itself is generally considered harmless, improper execution or excessive pressure could, theoretically, lead to complications. Jaw pain, muscle fatigue, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) discomfort are potential risks associated with any activity that involves sustained muscle exertion. The lack of professional guidance and supervision is a significant concern. The reliance on self-teaching through online resources introduces the possibility of incorrect technique and potential harm. People are encouraged to consult with a qualified dental professional or orthodontist before undertaking any new practice that could potentially influence facial structure.

The effectiveness of mewing, even if demonstrated to be partially effective, likely varies depending on individual factors. Age is a significant variable. Younger individuals, whose facial structures are still developing, may be more likely to experience positive results than older individuals. Genetic predisposition also plays a role. The shape and size of the jaw, the alignment of the teeth, and the overall facial structure are largely determined by genetics. The practice of mewing is more likely to produce noticeable changes in individuals with less-than-ideal facial structures. Other health factors, such as overall muscle tone and the presence of any underlying medical conditions, may also influence the outcome. It is important to establish realistic expectations before beginning the practice.

The practical application of mewing involves consciously maintaining the correct tongue posture throughout the day. The entire tongue should be pressed against the roof of the mouth, including the back third. The teeth should be gently touching, or slightly apart. The lips should be closed and the individual should breathe through the nose. Achieving this posture consistently requires practice and discipline. Many proponents suggest starting with short periods of practice and gradually increasing the duration as the muscles adapt. A focus on developing awareness of tongue and facial muscles is very important. It is also important to make sure you are breathing properly by taking the nose-breathing habit. Some people might find it helpful to use a mirror to monitor their posture in the beginning. The overall commitment and consistency are essential to see any potential results.

While the claims surrounding mewing are often presented with confidence, its crucial to approach them with a degree of skepticism. The "before-and-after" transformations depicted in online materials are frequently compelling, but they lack the scientific rigor required to establish definitive proof. The lack of robust research, the potential for misleading visual evidence, and the absence of professional oversight raise significant questions. While the practice itself may not pose an immediate health risk for most individuals, the unsubstantiated claims and the potential for unrealistic expectations warrant caution. The practice of mewing does not replace the care and advice of a qualified dental professional, and it's important to always consult with one if one is planning to incorporate this technique into one's routines. It's recommended to be aware of the limitations. The practice, however, could contribute to better oral health practices.

In conclusion, "mewing before after" remains a topic shrouded in both enthusiasm and uncertainty. The practices appeal lies in its accessibility and the promise of natural facial transformation. However, the scientific evidence supporting these claims is insufficient. The anecdotal accounts and visual comparisons, while intriguing, lack the objectivity and control necessary for reliable conclusions. The lack of robust research, the potential for misleading visual evidence, and the absence of professional guidance all contribute to the complexities of the topic. Those considering mewing should proceed with realistic expectations, an awareness of the limitations, and a healthy dose of critical thinking. Further research is needed to fully assess its efficacy and safety. In the meantime, it's important to prioritize good oral health practices, and to consult with dental and medical professionals for proper facial growth concerns.

Please note that the following table is provided for illustrative purposes and does not represent information about a specific person. If more information or a table for a specific individual or organization is desired, please provide the relevant information.

| Understanding Mewing: A Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| Concept: | A self-described facial posture exercise, involving conscious tongue positioning against the palate. |

| Proposed Benefits: |

|

| Mechanism: | Consistent tongue pressure is believed to stimulate bone remodeling and encourage forward growth of the maxilla and mandible. |

| Scientific Evidence: | Limited; most claims are not supported by robust, peer-reviewed research. Primarily based on anecdotal evidence and visual comparisons. |

| Risks: |

|

| Key Considerations: |

|

| Expert Advice: | Consult with a dentist or orthodontist before starting the practice, particularly if you have underlying dental or jaw issues. |

| Further Reading: | PubMed Central (NCBI) - Scientific Research Database (Search for related terms, but be critical of the conclusions.) |